‘Certainly this year of 1666 will be a great year of action, but what the consequence of it will be, God Knows,’(1) Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary at the beginning of the year.

The astrologers had been long predicting 1666 as a year of cataclysm yet there was no need to look to the Bible or the motion of the stars to recognise that the City was suffering. The scars of the plague year, 1665, were slow to heal and the contagion was now spreading out to the rest of the nation. Drought gripped the City during the summer and by August, St Mary’s on Fish Street was taking donations for prayers for rain.

In the early hours of Sunday, 2 September, six days after that meeting in the Churchyard, news reached England of another battle out to sea between the English Navy and the Dutch. The impetuous British Admiral, the King’s cousin, Prince Rupert, had attempted to engage the enemy off the French coast but as the Dutch ships hugged the coastline outside the port of Boulogne, a gust of wind attacked the British sails, cutting their lines and sending the fleet into disorder.

The storm then continued eastwards, hitting the coast of Kent and travelling up the Thames estuary until it arrived at London that night.

One way to divide up the sheep and goats of the Urbanist community is to divide them up between those who learnt the city by observation, watching the city as it actually is, and the measurers: those who develop quantitative standards in order to make seemingly objective conclusion on how the city works. There seems to be a deep tension that goes beyond the simple division between Jacobs-ists and smart city or IoT salespersons. It is not the problem of ethnographic immersion versus the tyranny of counting.

A couple of summers ago, I found myself standing on the corner of Lexington and 53rd Street, Midtown Manhattan. I was taking part in a project for the architect Jan Gehl, watching the people who were walking past, trying to get a sense of how people used this part of the city as a place of work, home, a non-space to be crossed at pace. Jan Gehl is one of the most interesting thinkers – and designers – of our contemporary city. His work can be found across the world: from Strogets a large pedestrianised area at the centre in his hometown of Copenhagen, to the recent opening up of Times Square, delivering this central space back to the public. Gehl passionately believes in reviving the life between buildings, to nurture the corner, bringing people back into the city, and allowing them to bump into each other and thereby to become citizens.

On that hot July day I counted pedestrians and bicyclists. I noted who was sitting down, and whether they were in pairs, or groups. What were they up to – talking, smoking, waiting? It was these observations that a sensor or a monitor could never pick up. GPS and wifi triangulation can only tell you that a phone and its user is in a certain place at a certain time. Face recognition and voice recognition software as well as an app developed by Qualia can be used to measure your smile. Nevertheless the algorithm is not good enough to know if the expression is fake or real, or whether you can experience pleasure without smiling. The human element is lost somewhere between counting and observing.

What I was watching was civil society in action, going about its everyday life. I was marking down how people used the public space, notes that would possibly go on to inform Gehl’s ideas on how to improve the use of this place, how to encourage more people here, or to manage the human flow better.

Contrast this with the news last year when UNHabitat announced that it had devised a series of test scorecards alongside the mega corporation IBM and engineering firm AECOM to develop best practise against climate change. Vulnerability to epidemics, work on flood defences, tax efficiency- everything would be marked numerically as part of the city’s resilience profile. The announcement included the news that Coimbatore, India, will become the first city to sign up for the initiative. A high score would prove that the city was future proofed, more than likely having spent millions on the latest technology to mitigate against disaster.

In the same month, the ISO, the Swiss based International Organisation of Standards, that sets international specifications for everything from the design of globally functioning plugs to the abstract benchmarking of management quality, announced that they had devised International standards for cities. ISO 37120:2014, will be a means to compare and judge the performance of any city on a number of criteria from economy to water, waste and sanitation. As the marketing brochure announced, the standard, ‘will help city managers, politicians, researchers, business leaders, planners, designers and other professionals to focus on key issues, and put in place policies for more liveable, tolerant, sustainable, resilient, economically attractive and prosperous cities’.

It has become increasingly popular to measure cities and there is an emerging industry in ranking world cities: a proliferation of liveability indexes; most expensive city; best city to do business; most popular amongst ‘Individuals of High Net Worth’; most creative. All these rosters reduce cities to a set of criteria. But how do we measure such a complex concept as a public space? Can we really quantify what makes a city ‘happy’?

Data is picked up by your bank cards, mobile phone, GPS, and face recognition software. Sensors, such as that developed by the Finnish IndoorAtlas, can map the interior of a building from the outside, promising that they will soon do for houses what Google Streetview does for our streets. High above the metropolis – as during the Olympics in London, as well as any major occasion – drones circle above unblinkingly watching the action 1000fts below; not all of them will be delivering parcels (both Amazon and Google are developing drone delivery services). Last July, the British government rushed through emergency legislation, DRIP, to allow the security services to continue to dragnet all our private data. In the UK you can now face jail if you refuse to hand over your password to the police.

For a start, Big Data collects lots of data but not all, it will therefore always be working with an incomplete set. Therefore it must create an algorithm that makes predictions on the basis of means and calculated averages. Thus when when a corporation pores over your data, they are looking at the agglomeration of averages that make up many but not all the choices, decisions and mishaps that mark your life. But you are not a collection of measurements, collated by the sum of all your outcomes divided by the number of events counted; and your day is never a sequences of average calculated moments. Thus Big Data is never more than a misted mirror, reflecting only a partial shadow of your complex self. How can this possibly be a better, or more efficient, way to run the city?

Secondly, this has a direct impact on the way we approach the city and its public spaces. In particular, this gathering of data will have an influence on how we design future places. The example that I want to use here is how the quantified city is being measured in terms of the tiny surges of hormones in our brains. In recent years neuroscientists and epidemiologists have started to chart how certain parts of the city, and a variety of urban experiences, affect the production of dopamines – such as oxytocin – that alter the patterns of the brain in response to stress and pleasure.

For example, there are a number of studies that explore the brain’s response to differently designed forms of privacy, a place to retreat away from the noise and bustle. What these studies seem to suggest is that we need to design private spaces that flow and connect with the public. Also looking at public streets, similar studies have shown how a variety of frontages at street level, and green spaces, produce a powerful chemical response in users’ brains. This work is already informing design strategies for public spaces around the world, such as in Vancouver that often sits high on liveability rankings.

The problem begins when this ‘happy city’ is defined by someone else, circumscribed by systems of universal ‘feeling’. Who decides what happiness is, and whether your happiness is the same as mine. In this chapter, in contrast to the prevailing thinking, I will show that this kind of design strategy produces the opposite; spaces where we must all be the same rather than places where we can all be ourselves.

So what does observation offer that is different, yet still useful to the average urbanist? As I pointed out in the previous blogpost about William ‘Holly’ Whyte: the work conducted outside Sakes 5th Avenue was ground breaking in its time and fits in with similar projects such as Jacobs’ discussion of the ‘ballet’ of Hudson Street as recorded in THE DEATH AND LIFE OF GREAT AMERICAN CITIES. At the same time Gehl was also watching people using Strogets and trying to work out why this new pedestrianised area was so successful. His conclusions were simple: people come to places where other people are.

This can appear quite a minor observation, but it a deeply profound truth that quantification at any level could never surmise. It gets to the heart of what a city is, and who the city is for. Reading Peter Laurence’s wonderful new biography of Jacobs he makes a good case for her stance not as a complete rejection of modernism or functionalism but a ‘functionalism of the particular’. The building, the street, the neighbourhood, the city, is not just one thing and to reduce any form to a single manifest function (or number) encourages a fragility that comes with closed systems. If only one question is asked and therefore be answered, then the project is bound to fail.

Observation encourages an appreciation of the complexity of the city beyond the numbers. The fact that we have the technology to do this job for us, does not mean that it can achieve the same outcomes. There is a still a gulf between smart technology and the city.

In 1969, William H Whyte, the author and former editor of Fortune magazine, started a new job at the New York Planning Department. Previously, Whyte had made his name in the 1950s with a controversial bestseller, ‘Organisation Man’, which proposed that the conformity of white collar life in America was crushing the rugged individualism the nation prided itself on. He had also anatomised the allures of suburbia, conducting closely observed studies on how these emerging neighbourhoods were transforming cities, and not for the better. As he entered his new role, he decided to conduct a series of experiments in the heart of the city.

Rather than assume that his office of planners, architects and transit specialists knew everything that there was to know about New York, Whyte hired a group of students from Hunter College, part of the City University, whom he stationed at various locations around the city. Their instructions were to watch how people came and went, how they used the city, how they conducted their ordinary urban lives. The results were a revelation.

Take, for example, the results of the observations that Whyte’s students made on the street corner outside Saks 5th Avenue, one of the most prestigious department stores in Midtown Manhattan. In the students’ illustration of the flow of human traffic over four days in summer, each dot represents a conversation, a moment when two people bumped into each other stopped and then had a chat for longer than two minutes.

According to this image, more often than not, conversations happened in the most inconvenient and unlikely places: many occurred just outside the front door of the store while the majority -some 57% – were conducted at the street corner; in effect these people were blocking the most congested place where other people were trying to cross the street, to turn, to move.

For Whyte, these observations proved that people rarely used the city in the ways intended. Instead they created their own public spaces, in which they played out moments of intimacy and connection. The city is made of such unexpected moments of gentle chaos.

They can be charted by desire paths that are scratched on the map of the city by common use rather than design. Whyte’s experiments showed that people do not behave in rational ways, and follow the planned logic of places, but rather that they find their own ways to get around the urban landscape, carving out their own pathways to citizenship.

In this moment of coming together, on the corner outside Saks 5th Avenue, one can read the story of the contemporary city, caught between a vision of the efficient, smooth metropolis and how it actually is. Here we see that the city is very different to the way we are told it is meant to be. This should be a profound moment of realisation for those who know more about the city that you think and who will be in a position to determine their future in that place: you.

*

I wish to celebrate the city corner in all its messy, human, contingent and unplanned joy. When we are informed that the story of the city is an economic table to be audited, or a circuit board defined by technology, it is the everyday life on an ordinary corner that reminds us that the metropolis is a human place. It is a place where people come to make a home. It is a refuge for some, a last resort, and for others, a new start. The city can be a lonely place to the lonely, and too noisy for those that need a little peace. It is a surface that needs to be traversed, or a mystery that reveals itself coquettishly. It can be the cruellest place on earth, but also our best hope for the future.

When we think of all the beneficial qualities of the city throughout history, it is its status as a meeting place, where two paths cross, that is the most compelling. Put simply, cities are places where strangers meet, and when that happens something extraordinary occurs. By coming together, learning to live and engage with each other on the street corner and the public spaces of the metropolis, we learn the rules of citizenship, the essential practises of how to get along. In addition, as we meet in that place, so we collectively become more than the sum of our individual parts. It is only on the corner where we can build our future civil society.

Many of these urban identities emerge from the life of an ordinary street corner. In an interior space – a room – the corner is the private place, but outside, on the street, the corner turns out to be the social space where people congregate. It is a place for crossing; it is the end of the block, where one reaches the boundary of the neighbourhood; it is where police surveillance watch for crimes, (not least in Chicago where the authorities plan to have a camera ‘on every street corner’ by 2016). It is where you can find the local shop that serves the community. A jumble of streets signs, and locators that connect this place with the rest of the city as well as a diverse array of different people that come together, including those on the margins, forming into what may be a community.

All the city comes together on the corner. This is where the creativity of the city emerges through chance encounters and serendipity, with people bumping into each other and exchanging good ideas, trading half notions that reveal something new. Here one can find the source of the city’s economic genius.

And yet for so many contemporary urban thinkers, the management gurus and Silicon Valley prophets, this human huddle at the meeting place of two roads is a problem. To them, the acquaintances and button-holers outside Saks 5th Ave got in the way, blocked the paths and caused obstacles for others. These hurdles, it is reported, are barriers in the creation of the optimised city where technology makes every moment ergonomic.

In this idealised city, there are no corners, simply smooth flows of data that improve productivity at every turn. This deeply human meeting place stands in opposition against the gospel of the new era: a liturgy of connectedness, of lean start-ups, collaborative capitalism, pro-sumption, and the advantages of a Big Data system that collates every scrap of information to create vast data sets to predict our collective behaviour.

We so rarely think about how technology changes the actual places where we live – the city. Nor do we consider how these devices influence our own behaviour in these spaces. None of these interventions come without consequences, yet they have the potential to reformat space, time and indeed ourselves. What are we to do?

The things that make up our everyday lives are each like single objects dropped into the seas of our lives; each breaks the calm surface and creates a ripple that spirals out from our lives into those of others. The ruffled waters are often choppy as the impact of our days accumulate; and the ripples that form are dense and complex patterns, which may appear on the edge of chaos.

We need to be able to read this turbulence better, much like a sailor who watches the surface of the water in order to read on it the bluffs and winds that encircle the boat. The best way to navigate the city is to understand its role as a street corner, where many avenues connect, both in the digital and real world, providing a space for our interwoven lives. It is here that the main currents and flows of the city churn and combine and become thing new again.

There is currently a campaign against the redevelopment of the Bishopgate Goodsyard in Shoreditch. Ironically this spot of ground,has always bee a problem. Originally devised as a passenger railway station in the 1840s its location at the end of Shoreditch High Street never made it close enough to the city to be useful. When, after Liverpool Street Station opened in 1874, Bishopsgate was transformed into a freight depot. Here it survived until a fire in 1964, and hence has stood unused at the heart of some of the most rapidly rising real estate in London. It is now surrounded by development, and there are plans afoot to profit here as well. Recently Mayor Johnson used his droit de seigneur to hurry along the planning process, jumping over the obstacles raised by residents and local councils. You can see more about the campaign here:

http://www.morelightmorepower.co.uk/

and the developers sales material here:

http://thegoodsyardlondon.co.uk/

However, what is interesting here is the campaigner’s use of Loss of Light as one of the key reasons to question the development. As plans for over 460 new towers are currently going through the system across London, this is going to become a growing issue here.

Consider the sense of joy that comes from sitting in a city square with the sun on your face. It is sometimes easy to forget how important sunlight is in our everyday lives. This was particularly a cause of debate in New York for as architect Michael Sorkin observes in his hymn to his home city, ‘Twenty Minutes in Manhattan’: ‘Much of the modern history of New York’s physical form is the result of debates over light and air.’ By the 1870s there were compaints that the high tenements that had been built to house the rising population were obscuring the sky and filling the air with a putrid stink. As a result a height limit was put on all residential buildings in the 1901 Tenement Housing Act.

But this did not stop architects who were developing the business district and in 1915 work started on the Equitable Building in Lower Manhattan to replace previous offices that had recently burned down in a fire. Out of the ashes the architect, Ernest R Graham, designed a neoclassical block that stood 62 storey tall above the city. As it was being built it soon became clear that the vast edifice would cast a shadow across seven acres, plunging the neighbourhood and the surrounding buildings into permanent darkness.

In response the New York government set out the 1916 Standard State Zoning Enabling Act that imposed limits on the maxmium heights of buildings, where they might be allowed to build as well a devising a code for ‘setback’, designing a building so that as it grows skywards, it also tiers inwards to reduce its shadow, as can be seen in the iconic designs for the Crysler or the Empire State buildings.

In the post war period, architects once again began to question these regulations. The modernist aesthetic, inspired by Le Corbusier, demanded bold regular blocks of pure glass and metal; rather than being ‘set back’ these new skyscrapers were being built within plazas so that the shadow would not interfere with other buildings. This new approach to the city was encapsulated by the Seagram Building created by Mies Van der Rohe and Phillip Johnson. Now, there was less emphasis on the experience of the city beyond the plaza that hugged the ankles of new skyscrapers, because it was assumed that everyone was in their cars; what sunlight one might encounter could be reflected from the shining glass of the modernist monuments onto the streets below where it would palely glisten along the crome finish of a polished cadillac.

Even in the 1960s campaigners were starting to discuss the idea of ‘solar access’, the essential right to sunlight as a key quality of life. In particular Californian architectural thinker Ralph Knowles was developing the notion of planning cities around ‘solar envelopes’ which determine heights and orientation of buildings according to the cyclical solar movements. In 2010 Mayor Bloomberg seemed to pick up on many of the key notions of the right to solar access, and how the persistent presence of shadows would impact on public life in the city. The excitingly titled CEQR Technical Manual used by developers in the city states: ‘Sunlight can entice outdoor activities, support vegetation, and enhance architectural features, such as stained glass windows and carved detail on historic structures. Conversely, shadows can affect the growth cycle and sustainability of natural features and the architectural significance of built features’

Environmental psychologists have spent a long time studying the impact of sunlight and shadow, conclusively showing that more natural light has an impact on the well being of workers or families within the space. In particular, scientists discuss the importance of sunlight for the body’s cicadian rhythm, or nature’s alarm clock. This is the natural process that regulates the daily biological rhythms, that is regulated by the hormone melatonin, secreted from a gland in the centre of the brain. The production of melatonin is regulated by light has an impact on conditions such as Seasonal Adjustment Deficiency. It has a strong antioxidant effect that protects DNA and works alongside the immune system in a number of experiments and even has an influence on the power of dreaming. This should encourage many architects to rethink the importance of sunlight within their design.

The fact that the Bishopgate development is a series of luxury towers that will overshadow the poor groundlings upon the street does not bode well for the future planning of London. Whether we come to work or play we might increasingly find ourselves walking in the shadows.

Following on from the two previous parts – Enclosure, and Privatization – this final part takes in the third and essential part of the process of the current transformation of London. Having marked off and then privatised the city, it seems obvious that those that are not welcome are excluded. This is often done in the name of ‘urban regeneration’ or even ‘place-making’. As we have seen in the previous parts, this process asks the question: ‘who is the city for?’ more and more often the answer is ‘not you.’

This is a subtle movement often spoken in positive language. It seems that the global cities of the world have agreed on the same algorithm for success, seduced by the quick-fix simplicity of TEDheads who can transform the city’s problems to an opportunity in 17 minutes and a smile. Attract the Creative Classes, they are told; build an art cluster; a tech city; invest in smart technology. All these off-the-shelf solutions turn the city into a corporation, offer a management strategy, and pushes questions of democracy into the small print describing ‘life style choices’.

Over the past few years, I have attended breakfast briefings in City of London head offices, spoken on platforms and attended ‘unconferences’; I have clicked through dozens of policy documents for new cities – to revive Rust Belt US, say, to ‘green’ Amsterdam, or to vault China into the global marketplace and to launch India’s ambitions for 100 tech cities by 2030. I have attended a Smart City conference in Buenos Aires where I spoke on a panel with representatives of multinational corporations, global engineering firms, local entrepreneurs and faculty deans; all hoping to push their city into the future, to own the right to be called ‘world class’. I have spoken at the top of the Shard about the future of London, and at the LSE Cities school. More often than not, I feel that we are having the wrong conversation. And there is a failure to engage with the real issues that face us today.

The term, gentrification, was first used in the 1950s by the sociologist Ruth Glass to describe the regeneration of post war Bethnal Green. In the 1980s we saw the development of sites like Canary Wharf and Docklands, that drove whole communities out of the city. In this instance, government and local councils worked with developers in what might be called state-driven gentrification. Then, in the 1990s, the architect Richard Rogers was named head of the Urban Task Force to rethink the social make up for the city (it was said that he spent more time in the Mayor office than the head of the Met police). He developed ways of thinking about revive the inner boroughs of the city, making denser communities with more attractive amenities.

This process of regeneration hoped to revive poor neighbourhoods by attracting the middle class back into the centre rather than the suburbs. Thus the inner city was made available to the young, the educated and creative. But this came at the expense of those who already called these neighbourhoods home. As a result, the story of gentrification in London is also one of race, for it is the ethnic minority communities that have been most affected by these machinations.

Carpenter Estate is more than a train ride from the City to Stratford. It was only a short walk from the station, turning your back upon the hubbub of the Westfields shopping centre, crossing the tracks and making your way to the deathly quiet of the Carpenter Estate, less that 500 metres away from the 2012 Olympic site.

It feels as if I am moving between worlds. The square was quiet, only disturbed by a couple of kids on bikes, but there was little noise or anyone stirring. I went into the shop, the keeper was standing at the till but did not look up from the TV screen that was under the counter. We spoke briefly but he could only repeat what I had already seen: most residents had left; only the last few remained. This used to be a vibrant community but it was now ruined.

The Estate has been under threat since 2001, with consultations, public meetings and assessments. But every solution has been deemed too expensive, unfeasible. In 2010, it was included in the Stratford Metropolitan Masterplan, part of the Olympic regeneration scheme. This included plans to replace the community with a new campus for University College, London.

The expulsions started in 2006 with the clearances of the two tower blocks. The council said that they had become infested with ants, or that they had found evidence of asbestos, and so the flats had to be emptied. Walking around them today, the ground floor windows have been blocked up but you can see that some of the upstairs flats are still occupied. You can bet that the council have cut off the power to the elevators ‘for safety reasons’.

Elsewhere across the estate you can see evidence of ‘de-canting’, but it is the eery quietness of the place that really hits home. For a few weeks in September last year there was lots of noise here as the Focus15 mothers – local residents, some of them mothers, who had decided to squat the empty houses rather than face eviction. They wanted to make a stand because the alternative was being forced to live miles away for family, friends, work and community.

The newspapers came down, and so did Russell Brand. But now the story has moved on, and the estate has to get on with its inevitable decline. This place is just one in a growing number of crisis points around the city. But at the same time the voices of resistance are also growing: from street protests, squatters occupying homes to organised resistance and residents defending their rights in court. It is in these moments of defiance that the hopes of the city are seeded.

In a series of recently leaked documents discovered by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, it was calculated that over 50,000 families have been removed from London as a result of welfare cuts, soaring rents, and council compulsory purchases since July 2011. In each case, they have been uprooted from their communities and either provided with new accommodation far away, or forced to find their own new lodging wherever the could afford it.

For example, between July and September last year, 423 families were sent out of London, some relocated as far as Manchester. Mayor Boris Johnson was criticised in 2011 when he claimed that his own government’s policy would cause ‘Kosovan-style ethnic cleansing’. As history shows us, the process of enclosure always includes the violence of clearance, or as the sociologist, Saskia Sassen’s call it: ‘a savage sorting’. This is what is happening in London today.

Johnson was not so perceptive when he highlighted the problems of inequality in the capital. it is now calculated that top 10% in London are over 280 times richer than the bottom 10%, and this divide is growing: in the last 7 years share of income for the bottom decile has fallen over 25%. Mayor Johnson’s most recent new Draft Housing Strategy [December 2013], noted that 80% of all housing stock in London is currently affordable solely to the top 20%. Nevertheless, Johnson preached: “I don’t believe that economic equality is possible; indeed some measure of inequality is essential for the spirit of envy and keeping up with the Joneses that is, like greed, a valuable spur to economic activity.’‘ For the Mayor, the solution is building for those who are in search of investments, ignoring those who can no longer afford even affordable rents.

This policy is hardwired into the plans for the future. In an unequal city it is more difficult to get access to housing, healthcare, education and the simple task of moving around the city, to get to work. Inequality is connected to higher crime and murder rates, increased levels of mental health problems, teenage pregnancies, obesity, and a reduction in social mobility, poorer exam results, the decreased likelihood of voting in an election, and, more perilous of all, how we die. Thus, inequality reveals itself in the everyday life of the city.

This policy of exclusion can be seen in subtler forms: the poor door at the side of newly built blocks that offer a separate entrance for the apartment owners and those who rent the affordable dwellings that the developers were forced to include in the project. It is also found in the eminent domain payments for local residents to move out of an area that is to be redeveloped. The compensation may be fulsome but is never enough to stay in the same neighbourhood. Recent news stories highlighted the addition of ‘homeless spikes’ outside a storefront to dissuade panhandlers. Street furniture is now designed to discourage long rests, or riveted to the ground so they can not be moved. These surreptitious methods of sorting out establish an uneven geography of who belongs and who does not. And in the end, rather than a safer, happier place, it creates an unfair city that highlights difference as a reason to distrust the others that we come across.

Expulsion – of those that do not fit, those who cannot afford the spiralling costs, those who are not productive or efficient enough – force us to ask the question of who the city is for.

The result is that it is the poor and the most in need are being pushed outwards to the fringes of the city. Where once the discussion was the blight of the inner city. In a report in 2012, following the riots of the previous year, of the 430 neighbourhoods that have seen dramatic rise in deprivation, 400 of them are on the periphery of the city. As the academic Alistair Rae notes: ‘it would appear that centrifugal forces are currently helping shift poverty from inner to outer London’.

Back in the inner city, the process of expulsion goes hand in hand with the policy of ‘Place-making’, which has become the dominant mantra of contemporary urban design. The loss of public space threatens our abilities to be citizens and to engage with the city as a political space. This threat is written in the hidden regulations that restricts usage, such as PSPOs, [public space protection orders], passed by the UK government in 2013 without anyone noticing that they give local authorities unchecked powers to control public spaces, marked by CCTV cameras and the ominous presence of security in hi-vis vests.

Last autumn I attended the the Bristol festival of the city. Find here a link to an interview I did with the organisers:

This is the second part of a series of essays on the process of transformation in the city today. the first essay looked at: Enclosure: . Here we look at how – once enclosure has happened, it goes hand in hand with privatisation. In the future we will look at expulsion as the logical conclusion of the process.

Jane Jacobs wrote: “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.”

The inequality of housing, a place to call home, is the most stark indicator of our divided lives. there is nothing in the nature of cities that dictates that there has to be this geography of difference. Inequality impacts on all parts of the urban landscape and it is the have-nots who do not have access to parks and green spaces, nor have the luxury of privacy and adequate housing.

In Mayor Johnson’s Draft Housing Strategy [December 2013], it is noted that 80% of all housing stock in London is currently affordable solely to the top 20%. The same imbalance between supply and demand can be found everywhere. Johnson’s stewardship can be typified by the promise to rid the city of poverty and blight, but without understanding the causes of the problem. Throughout the administration the problem of poverty and inequality was depicted as one of neighbourhood decline, localised economic inefficiencies, rather than human desperation in the face of deplorable unfairness. In both cases the role of planning was seen as clearing out, up zoning and privatisating under producing neighbourhoods. The emphasis of ‘quality of life’ issues that hoped to attract investment, creativity and wealth, never attempted to address the actual facts of inequality. By packing the top end of the city, this did not raise up the rest but drove out and stamped down those that needed the most help.

For example, plans were announced last summer for the 74-story Hertsmere Tower in Docklands were announced offering 714 luxury apartments, the most expensive clocking in at over £10 million. While Mayor Johnson has given the green light to the £800 million project, there are 23,000 on the waiting list for affordable and social houses in the local Tower Hamlets council. Elsewhere in London the demand is at critical levels without any appearance of a solution.

‘Who is the city for?’ has become one of the most urgent questions in our current crisis.

This shows that much of the current development of the city is not for living, but for capital accumulation. The house is no longer a home but an asset. For example, since 2000, of 2.9 million houses have been built in the UK, 2.5 million have been sold to landlords. This leads to the extraordinary statistic that, in a recent London Poverty Survey, 28% now live under the poverty line.

–

You can not open a newspaper without a story about the next calamity in the housing crisis, or how we are becoming more unequal, yet these are signals of a much deeper problem. London is living through a period of rapid enclosure: the spaces where we live our everyday lives are being measured, given a value, and sold to the highest bidder. This process of financialisation and privatisation turns a universal common wealth into a portfolio of assets, to be traded in a global market. This process has seeped into every corner of the city. It defines who is allowed to be part of the metropolis; it affects our relationships with each other, the places where we come together: home, work, public spaces and the corners that we hope to keep private.

That we are more unequal than ever before is now incontestable.Thomas Piketty’s deceptively brilliant equation that: R is greater than G (when R stands for capital investment, and G represents wages) shows that since records have been collected, those who own have had it better than those who work. The statistics tell us: since 1980 the super rich have paid themselves more than ever before, while real wages had declined for everyone else. As a result, in the aftermath of the great recession of 2008, 95% of all economic growth has gone into the hands of the 1%.

Yet, these statistics do little to bring the reality of this imbalance into focus. It is difficult to appreciate such desperate differences at a distance. Even when it is stated that the top 10% in London are 280 times richer than the bottom 10%, it is difficult to perceive this balance. In New York, the top 5% earn 88 times more than the bottom 20%. In both cities the poverty level is between 20-25%, far above the national average. Yet it is difficult to see the human face behind such numbers. It becomes clearer when we give inequality a location.

For example: according to a recent study conducted by University College, London, it is possible to chart the rise and fall of life expectancy along the underground rail line, the Central Line, that runs through the middle of the city from west to east. The map showed that there is a 20 years difference in life expectations that comes from living either in the centre, Oxford Circus, or around certain tube stops in the East End of the city, Mile End. The distance between these two locations is a train journey that takes less than twenty minute, yet it can determine a dramatic gulf in longevity.

The city magnifies inequality and then gives it geography. It is where wealth is made and also the place that the poor come to; and often they have to live desperately close to each other. Yet income inequality within the city is more than just a register of varying levels of wealth amongst neighbours. The consequences of inequality goes to the heart of every aspect of the city: it defines the human landscape and determines the distribution of opportunities, turning the advantages of the city that should be available to everyone into a rigged lottery.

According to Globalisation and World Ranking Research Institute London, alongside New York, has been given the highest status of ‘Alpha Double Plus’, as central network points within the swirling global marketplace. It is a city where everyone wants to do business, and a destination for bodies, goods, money from across the planet. According to the 2014 Savils Wealth Report, the city is a major destination for the world’s Individuals of High Net Worth [IHNW]. For urban economist, Ed Glaeser, this makes it the best place to come to find business, culture and a husband.

At the same time, in other parts of the city, in the face of the fact that Britain no longer made anyway, the only commodity that could spread the economic good story was the ground beneath our feet. Owning a house, and buying shares of one of the recently privatised national utilities was presented as a badge of economic success; it was the smartest investment around: as escalating house prices outstripped wages, homes became lucrative assets. The right-to-buy initiative in the 1980s, that sold council properties at below market rates, also flooded the market with properties that could be turned into profit. Yet these properties were not replaced: the last time we had enough houses for everyone was 1971, forty-four years ago. Since then we have built too few houses, further pushing the demand skywards.

This process turned London’s very soil into one of the safest investment in the world. The result are the ghost houses of the super-rich, the privatisation of public spaces, the savage sorting of the city where ownership determines who belongs and who is no longer welcome.

In the end, the damage of this rampant privatization is not to the fabric of the city but, more urgently, to us. Access to the metropolis has turned from a right to a privilege policed in ways that we cannot intuitively understand. This not just affects the spaces of the city but also the way we are allowed to behave in them.

In a series of 3 short articles, I want to look at what I see as the current dynamic happening in London: Enclosure, Privatization and Expulsion. These three processes combine together. It is a system of circumscription, transformation and then violation. Often this is done in the name of social benefit, as a way of preserving or regenerating the nature of ‘place’ or neighbourhood’. In effect, it is not different from the process of enclosure that haunted the 18th century.

I fear that we are starting to lose the things that make our cities such extraordinary places, places that bring out the best in ourselves and each other. London serves as one of the most observable test beds of the dilemmas in 21st century urbanism.

It does not have to be this way. An unfair metropolis is not the price we have to pay for urban living. We must have the confidence to believe that change is possible, and it is in our hands.

Enclosure

At the beginning of the new millennium the chief planner of the City of London, Peter Wynne Rees, claimed that we were living through ‘a second Great Fire of London’. With this comment, he foresaw the transformation of the financial centre from a historical jumble of offices to a vertical city of skyscrapers. When the Gherkin topped out in 2004, London was still a low lying skyline; today there are plans for over 250 towers stretching from Greenwich to Croydon. Yet what kind of city is this? What have we gained as a world city, and what have we lost? This chapter looks at how London has become a city within a city: an enclave for the 1% who wish to enclose and privatize the metropolis around them.

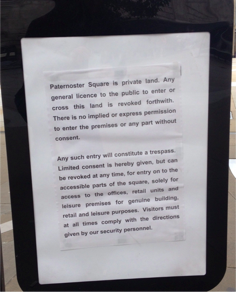

One afternoon, for example, walking into Paternoster Square, a popular tourist spot next to St Paul’s Cathedral with cafes and shops, as well as the offices of the London Stock Exchange and Goldman Sachs, I encountered a placard that read:

This is nothing new. In the early nineteenth century the Northamptonshire poet John Clare, son of a farm labourer, wrote a series of elegies ‘On the Enclosure of the Commons’, which mourned the damage by enclosure that had be done to the countryside as well as to the labouring poor:

These paths are stopt – the rude philistine’s thrall is

laid upon them and destroyed them all

Each little tyrant with his little sign

Shows where man claims earth glows no more divine

But paths to freedom and to childhood dear

A board sticks up to notice ‘no road here’.

We are currently seeing a full-scale enclosure of the twenty-first century city, with an impact as calamitous as that suffered by the eighteenth-century countryside. This new enclosure redefines not just the places that are privatised but also the behaviours that are and are not allowed there. This can be seen most obviously in the development of gated communities, ‘secured-by-design’ housing, and the rise of privatised public spaces.

This process of enclosure has a history that goes back to the office building boom of the 1960s, when developers were given rights on the ground around their buildings as a means to protect their investments. But this mechanism spread from plazas and ornamental flower beds linking the street to the foyer to whole sections of the city. The writer Anna Minton has identified the intentional silences in recent planning law that has lead to the enclosure of central parts of our city: streets, squares and now whole neighbourhoods. [see: http://howtoworktogether.org/wp-content/uploads/htwt-think_tank-anna_minton-common_goods.pdf]

What happens when we are no longer allowed to be in our own cities? Last year the British parliament passed an Act that made Public Space Protection Orders (PSPO) law, allowing local councils to designate certain areas under certain rules and regulations. Since the law was passed, for example, Dover council has enforced a rule that all dogs should be on a lead; in Oxford, anyone under twenty-one is banned from entering a specific tower block in Forest Hill. It is no longer possible to protest in the public square outside Croydon Town Hall. There were even recent attempts to ban all homeless people from the public areas of Hackney.

I recently argued this question in public of what makes public space with a group of leading developers, and feel strongly that this is a topic that is not being discussed enough. While one must acknowledge the developer’s consideration for the public realm: a commitment to community building and developing open spaces, and environmentally sound designs. Often, this vision is flawed, and short sighted. In a business where the long term is measured as between 5-7 years, we cannot hope to rely on the current status quo to provide good public spaces.

This raises the problems of ‘Place-making’, which has become the dominant mantra of contemporary urban design. The loss of public space threatens our abilities to be citizens and to engage with the city as a political space. The alternative is only too clear to see: The Garden Bridge (sponsored by notorious polluting company, Glencore), the Cable Car (Emirate Air), the new Crystal Palace (Zongrong Group) – and even the Olympics (Coca Cola, VISA, ArcelorMittel, etc) – are eye catching additions to the city, but offer little social nutrition. The development of these seemingly public projects have been conducted hand in hand with the enclosure of the city.

We must find new ways of building open spaces for all that doe not have to involve the process of enclosure, and in this we must be aware of who these spaces are for. In this, the process of how these places are created is as important as finished space itself. The question of ownership can only be developed through a rethinking of the value of use.

The first time I visited Moscow was in September 2013, at the kind invitation of the Strelka Institute. [ the talk can be seen here: http://vimeo.com/79883918] It was my first encounter with a city that had loomed large in my imagination for many years. I was invited in order to talk about Jane Jacobs, a figure that has become central to my thinking about cities and what makes a good place. Therefore as I left my hotel and made my first steps into the urban realm, I was hoping to encounter the city on a number of levels.

The central plaza and streets of Moscow seemed very far from the more intimate neighbourhood spaces of 1960s Greenwich Village, Manhattan. As I explore in this book, Jacobs saw something of the deep flows of the city and explores what we might lose when we concentrate on making the city more efficient, more smooth. The well rehearsed image of the ‘street ballet’ of Jacob’s own home, Hudson Street, is a paradigm that should be nurtured wherever one goes. Yet this was very far from the vision that I encountered in central Moscow.

As I wandered along the streets that run alongside the Moskva, I found that I was weaving my way through cars that had been parked along the pavement area. Further along, as I attempted to cross one of the main roads, I discovered that I had to navigate a complicated sequence of manouvres in order to get back to where I was. I felt, as a pedestrian, the city was not revealing itself to me. The city had been taken over by the cars that now filled the arteries and flows of the city, reducing the pace of the city to a halting, grinding standstill. Many of the qualities of the city that make it so creative, human, surprising were being lost, and even those who wanted to encounter the city in other ways had to negotiate their routes around this dominant form of traffic.

In this, Moscow is no different from many of the major cities of the world. But what is the solution? In its 9,000-year history, the city has been the place where strangers have come together for multifarious reasons; but in that coming together, the city has become greater than the sum of its parts. This is what Jane Jacobs was describing when she talked about the ‘Ballet of Hudson Street.’ In an unforgettable description of what she saw and heard on an ordinary day standing outside 555 Hudson Street, Jacobs followed the traces of the complex city as it interwove in front of her doorway. What she discovered in is the genius of the city: connections and networks.

In the weeks before my arrival in Moscow, I was told, the Danish architect Jan Gehl had visited. Gehl had first explored his ideas of the life between buildings in his home city of Copenhagen. When he pedestrianised the central section of the city, Strogets, as recounted later this in the book, the locals felt that he was mad, and endangering the normal running of the city: how things ran. But it was within months that the success of the project was acknowledged: people came to this neighbourhood and made it the public forum of the city, if not the nation. This was a public space that people wanted to be in.

When Gehl went back and investigated why Strogets ‘worked’ as a public space, he watched as the locals wandered around the place, how they interacted and what they observed. He discovered that despite the general good spirit of the place, people undoubtedly stopped at the cinema to see what was on, sat in cafes and met their friends, window shopped and hung out: but the thing that interested people the most were other other. The key to a good public space is the understanding that we are hard wired to be together, and that something special happens when we gather: we become more than the sum of our parts. There are plenty of examples of this.

Charm Offensive, a 2011 study by the Young Foundation, recorded levels of civility in three different parts of the UK: a market place in one of the poorest boroughs of London, a new town in Cambridgeshire, and a selection of villages in rural Wiltshire. The study found that politeness is not a question of wealth or homogeneity, but of proximity and interaction. The marketplace in the East End of London, despite being a place of huge diversity, was also the place where everyone was willing to muddle along. There was equality amongst stallholders and shoppers to make this a good public space.

This seems to align with Richard Sennett’s mantra that we need good public spaces in order to learn the rules of coming together. For despite our deep desire to be together, we are not equipped at birth with the necessary tools for being the true social animals that our instincts tell us we are.

As an architect, Gehl sees that this is a design solution: if we design good public spaces, then people will come together. In Gehl’s study on Moscow ‘Towards a Great City for People’ that was published the same month as my trip [http://issuu.com/gehlarchitects/docs/moscow_pspl_selected_pages] placed the dominance of the car as the main problem of the city, estimating that the automobile took over 91% of Tverskaya space, and elsewhere in the city this proportion rarely rose above 20% of space given over to the human and social life of the metropolis. The report then goes on to develop ways in which to enhance the existing qualities of the city: historical heritage, quality of green spaces, while also developing strategies of how to deliver parts of the city back to the ordinary citizen, not stuck behind the wheel, cut off from the joys of street life. Gehl proposes a ways of ‘unlocking’ the treasure of Moscow, as if they are there already and need to be released.

But design is not the answer alone. The architect can not cure the ills of the city just by manipulating the structures and objects of the urban fabric. Everything about the city is political – this is unavoidable. It is often the attempts to de-politicise the city – to offer solutions without understanding the diversity and uneven landscape that makes up the city – that cause more problems than they cure. In ‘Cities Are Good For You’ I highlight the importance of the debates on inequality, trust and sustainability as central to the argument of what makes a fair city, a place that I believe that we all deserve.

By politics, I do mean the daily goings-on of City Hall that is essential to the good running of the metropolis and in the following chapters I explore some of the ways these can be improved, but I also mean a more personal, everyday form: the politics of everyday life.

An unfair metropolis is not the price we have to pay for urban living. We must have the confidence to believe that change is possible, and it is in our hands. This is why we must return to the politics of everyday life in order to find a way forward. It is this that Jacobs identified as the spirit of the city, it is also what the French philosopher Henri Lefebvre sees as the raw material from which transformative change can occur. Here, in our ordinary moments, we live a life in connection with others: neighbours, strangers, co-workers, corporations, government. We must rediscover the truth that these connections are what makes up our lives, and therefore everything that happens in the city is political. As Lefebvre notes:

‘true politics involves a knowledge of everyday life and a critique of its requirements. . . Everyday life is profoundly related to all activities, and encompasses them with all their differences and their conflicts; it is their meeting place, their bond, their common ground. And it is in everyday life that the sum of relations which make the human – and every human being – a whole, takes it shape and its form.’

The only way we can learn to be together and live together is by coming together. Yet this simple truth is increasingly under threat in our modern city.

I was reminded of the importance of social urbanism last summer when I heard the story of Erdem Gunduz, the young protester who, on the evening of Monday, June 17, 2013, walked onto Taksim Square, put down his rucksack, and turned to face the Ataturk Cultural Centre at the end of the square. There he stayed for the next eight hours, saying and doing nothing except occupying the space where he stood. In that moment he reclaimed not just the power of that public place–which was contested at that time–but also his right to be there, to be a citizen.

There is something important that occurs when we occupy public space. Not only does the action itself reclaim the urban place for the benefit of all, but it creates citizens, like Erdem Gunduz. Thus the idea of a truly social urbanism is one that combines place, action, and citizenship. The space can only be public because it has been reclaimed.

This calls for constant vigilance, as well as a new set of values that rewires the way we think about the city. These values might include trust, equality, and the right to the city for all. The relationship between trust and equality is indelibly interlinked. There can be no trust when there is “us and them,” the “haves and the have-nots”; trust is the glue that brings the city together and allows the nurture of civility.

As ‘Cities Are Good For You’ shows, these benefits of urban living are for all, but they are often hard won gains that need to be protected from the constant tides and demands of those who see the city as a place of exchange alone, and not a place that can make us better people. What breaks this trust is inequality, the loss of empathy, which we can see all around us in the contemporary city—and it is getting worse. Today, cities around the world display unprecedented levels of inequality in parallel to some of most stricken developing nations. By addressing these dangerous divisions, the steps we need to take to revive and rediscover the power of public spaces, and reclaim the city for all will become clear. For if the city is not for everyone, it benefits no one.

The books starts with questions: how do we organise ourselves when the institutions that once held us together no longer connect us? What are the rules that allow us to be together? And most importantly, who is the city for? These questions allow us to think about the city anew. This thirst for a fairer city must influence policy, design, social enterprises, urbanism and business. They inform the debate on the boundaries between private and the public space. They show the interwoven relationship between trust and equality in creating places and neighbourhoods. They are at the heart of the search for spaces that can be places of nurture, learning and creativity. It is only a democratic turn that can propose what makes a robust community, a place where people look out for each other.

It takes a city to prepare for an uncertain future, not only to survive but to flourish.

Do we really understand the impact of gentrification? The term was first used in the 1950s by sociologist Ruth Glass to describe the regeneration of post-war Bethnal Green in east London – today, gentrification can be found in the regeneration of poor neighbourhoods by middle-class families and businesses moving into the cheaper, traditionally working-class areas of the city. The inner city is made available to the young, the educated and the creative at the expense of those who had called it home.

Some commentators note that gentrification might be a good thing: a process that improves a neighbourhood over time. For others, it’s a natural process that happens as cities evolve. But more critical observers point out that displacement causes problems for health and community cohesion as existing neighbours are forced out, dispersed across a large area, often into places with worse conditions, poorer housing, bad transport links and massive demands on an already straining health service.

A report by the Centre for London, Inside out: the new geography of wealth and poverty in London, outlines how poverty rates have fallen since 2001 in many inner London neighbourhoods, such as Hackney, Haringey and Newham. The suburbs in England’s capital, meanwhile, are becoming increasingly impoverished and disconnected from the rest of the city.

However, the impact of gentrification on inner-city communities is not as straightforward as it sounds. Most studies have concentrated on the process of displacement and health specialists have long been aware of the dangers of this regime of expulsion. But, as recent reports indicate, displacement is not always as fast as we have assumed – and often overlooked is the fate of the vulnerable who remain, or are left behind.

Paris heatwave

Take, for example, the heatwave of August 2003, one of the hottest on record for Europe, which caused the 14,800 deaths in France. In particular the heat affected the very old and infirm, especially in Paris.

As well as age, there were other unexpected parallels between many of those that died. Many lived alone and during summertime – when most families are away for the holidays – without help. They also lived in buildings that had been built before 1975, often inhabiting small flats in the upper floors of the building. In this case, gentrification did not drive the old and infirm out, but up, into the poorly insulated garrets and worst grades of housing where there was no one to look out for them.

While studies often chart the impact of gentrification on health in a borough or neighbourhood, the process itself often happens street by street. This creates unequal places on a very intimate level, where huge disparities can be felt just walking down the road. The social and economic gaps between new neighbours are palpable, as privately owning “haves” crowd into the spaces of predominantly renting “have-nots”. Rents are raised, while landlords look for ways to push out those who cannot afford the new rates. This has long-term consequences for the future health of a city, creating places that reduce opportunities and promote exclusion. It demands an urgent rethink of health, education and housing services, especially in an era of increasing austerity.

One of the most dramatic examples of the inequality created by gentrification on a very local level can be found in the re-emergence of tuberculosis in cities. The most recent UK government report (pdf) on combatting the disease found fewer instances of TB over the past three years, following a peak in 2012 – partly due to better screening of non-UK born patients as they enter the country. However, the rates of TB among UK born patients has remained steady.

As the report notes: “TB continues to disproportionately affect the most vulnerable people in society, and the most vulnerable patients with TB continue to have the poorest outcomes … This highlights the crucial importance of tackling TB in the most under-served populations through systematic joined-up care between health and social services, the third sector, public health and housing.”

What’s particularly striking is that the highest density of TB victims are found in many of the more rapidly gentrifying neighbourhoods of UK cities, such as Hackney. Housing is key; the TB team at Homerton University Hospital notes: “Although Hackney has undergone rapid gentrification recently, there are still significant numbers of people living in deprivation and poverty, and the borough still acts as a magnet to migrants both legal and undocumented, many of whom join hard to reach, socially excluded groups.” The team is to be lauded for its efforts to find housing for TB patients, but it is likely to become increasingly difficult.

When we look at the effects of gentrification on health and wellbeing, we might be searching in the wrong place, or missing vital symptoms because we are not expecting them. The battle against poverty and inequality is being played out on urban streets. Gentrification creates poverty not only through displacement but also on our doorsteps, hiding poverty as it appears to regenerate a neighbourhood. But the poor and vulnerable do not disappear.